Faith and History

By R. T. Mckenzie

Actually, I have no idea how Abraham Lincoln observed New Year’s Eve, but I do have a strong suspicion about what passed through his mind as one year gave way to the next.

I spent this morning in a coffee shop with a book titled Herndon’s Informants. The “Herndon” in the title refers to William H. Herndon, Lincoln’s long-time law partner in Springfield, Illinois. In the aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination, Herndon became convinced that the country was transforming the late president into a mythical figure bearing no resemblance to the man he had worked alongside for nearly two decades. To prevent this crime against history, he set out to write a biography of his friend and partner that would set the record straight. He spent much of the next two years tracking down individuals who had known Lincoln personally. Herndon’s Informants embodies the fruit of that labor. Compiled and edited by scholars almost a century and a half later, it is a collection of more than eight hundred pages of written and oral reminiscences from more than two hundred and fifty friends, relatives, neighbors, and associates who claimed to know Lincoln well.

I’ve been working my way through this hefty volume for some time now, but two things especially struck me as I read this New Year’s Eve. First, countless informants independently testified that, although Lincoln was fond of well-known poets such as Robert Burns and Lord Byron, his favorite poem was by the little-known Scottish poet William Knox (1789-1825). The poem, “Mortality,” is a dreary litany of human hopelessness in fourteen ever-more gloomy verses. Knox’s main goal seemed to have been to remind his readers of the certainty of death and the vanity of life. Here is his first verse:

Oh! why should the spirit of mortal be proud?

Like a swift-fleeting meteor, a fast-flying cloud

A flash of the lightning, a break of the wave

He passeth from life to his rest in the grave.

Like the author of the Old Testament book of Ecclesiastes, Knox stressed repeatedly that death is no respecter of persons. In Ecclesiastes chapter 2, the Preacher observes that although “wisdom excels folly as light excels darkness . . . the same event happens to them all.” Hear Knox’s echo:

The saint, who enjoyed the communion of Heaven,

The sinner, who dared to remain unforgiven,

The wise and the foolish, the guilty and just,

Have quietly mingled their bones in the dust.

“Mortality” begins and ends with futility. The world it describes is a closed universe with scarcely a hint of a divine Author. Life is short and then you die. Here is the poem’s last verse, which Lincoln, reportedly, viewed as particularly eloquent:

‘Tis the wink of an eye — ’tis the draught of a breath–

From the blossom of health to the paleness of death,

From the gilded saloon to the bier and the shroud:–

Oh! why should the spirit of mortal be proud?

Lincoln learned “Mortality” by heart and recited it often. A storekeeper who knew Lincoln in the 1820s remembered him relating it. So did a lawyer who traveled the circuit with Lincoln in the 1850s. The latter recalled Lincoln saying that to him “it sounded as much like true poetry as any thing he had ever heard.”

In my reading this morning I also learned that, as a teenager, Lincoln had transcribed some ostensibly similar verses into his copybook. Reproduced exactly, they read as follows: “Time What an 'emty' vaper tis and days how swift they are swift as an Indian arrow fly on like a shooting star.”

Here again we’re confronted with the brevity of life, albeit from a very different writer, and for a very different purpose. If you don’t recognize these lines–as I did not–they come from the prolific English hymn writer Isaac Watts (1674-1748). Lincoln clearly wasn’t copying them directly from a hymnal–the misspellings testify to that–so it seems likely that he had heard the words sung and was doing his semi-literate best to preserve them from memory. They come from Watts’s hymn, written before 1707, “The Shortness of Life and the Goodness of God.” Here are all seven verses as recorded in an 1821 edition of the hymn-writer’s works:

Time! what an empty vapour ’tis!

And days how swift they are!

Swift as an Indian arrow flies,

Or like a shooting star.

The present moments just appear,

Then slide away in haste,

That we can never say, “They’re here,”

But only say, “They’re past.”

Our life is ever on the wing,

And death is ever nigh;

The moment when our lives begin

We all begin to die.

Yet, mighty God, our fleeting days

Thy lasting favours share,

Yet with the bounties of thy grace

Thou 'load’st' the rolling year.

‘Tis sovereign mercy finds us food,

And we are cloth d with love;

While grace stands pointing out the road

That leads our souls above.

His goodness runs an endless round;

All glory to the Lord:

His mercy never knows a bound,

And be his Name ador’d!

Thus we begin the lasting song,

And when we close our eyes,

Let the next age thy praise prolong

Till time and nature dies.

Significantly, the young Lincoln did his best to record the first two verses but then he stopped, even though the full hymn continues for another five verses. I found myself wondering why: Did his memory fail him? Did the unfamiliar labor of writing grow tiresome? Or did the poor youngster in Indiana find it hard to relate to the latter part of Watts’s hymn?

Although Watts’s hymn starts similarly to Knox’s poem, it eventually transitions to words of comfort and hope. As the hymn’s title suggests, Watts would have us understand the shortness of life in light of the goodness of God.

Yes, Watts agrees, our days “slide away in haste” and “death is ever nigh.” Yet that’s far from the whole story. God showers our brief sojourns with the hallmarks of His favor: mercy, love, and grace. And death–though inescapable–is not the end. We “close our eyes” to awake in a new age with a song on our lips for eternity.

One of the most repetitive observations of Scripture is the simple truth that our lives are short. We read that our days on earth are akin to a “breath” (Job 7:7), a “passing shadow” (Psalm 14:4), a “puff of smoke” (James 4:14). I think it’s good to dwell on this truth as the year comes to a close, but as Isaac Watts reminds us, we mustn’t stop there.

_________________________________________________________________________________

LINCOLN MADE HIS VISION CONCISE AND COMMUNICATED IT OFTEN

It's well known and documented that during the Civil War Abraham Lincoln, through his speeches, writings, and conversations, "preached a vision" of America that has never been equaled in the course of American history. Lincoln provided exactly what the country needed at that precise moment in time: a clear, concise statement of the direction of the nation and justification for the Union's drastic action in forcing civil war. In short, Lincoln provided grass-roots leadership. Everywhere he went, at every conceivable opportunity, he reaffirmed, reasserted, and reminded everyone of the basic principles upon which the nation was founded. His vision was simple, and he preached it often. It was patriotic, reverent, filled with integrity, values, and high ideals. And most importantly, it struck a chord with the American people. It was the strongest part of his bond with the common people. The most important sentiment, he felt, was "that sentiment . . . given liberty not alone to the people of this country, but hope to the world for all future time. It was that which gave promise that in due time the weights would be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that all should have an equal chance."

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Cat Clausen to Appear on "Backstory with Larry Potash"

This story appeared in “The Paper, September 2020,” by Bridget DeWaard

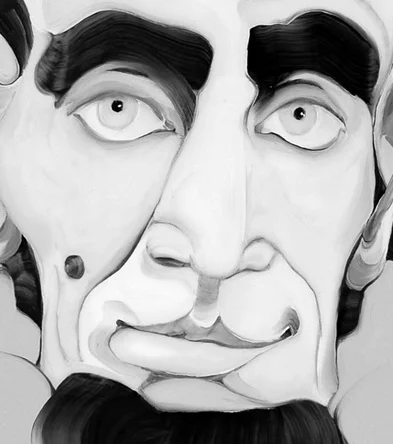

As the weather chills and we officially head into fall, get comfy, curl up on the couch, and catch a new episode of "Backstory with Larry Potash." Centered around our history and stories of the past, local artist Cat Clausen will be featured in the Saturday, October 10 segment, which explores Abraham Lincoln and the politics of his time.

"I remember being drawn intuitively to the tv one day, and catching just a bit of an interview with an artist painting beautiful art pieces onto the backs of people's jean jackets. The artist was asked, what's the concept here? Why are you painting on all of these jackets? And the artist said, almost immediately, it's always love," local artist Cat Clausen said, sharing how this simple interview became one of the most influential moments on her work.

In keeping with this concept, Clausen describes how she connects her famous historic muse to this direction. "Lincoln loved people, and he loved to encourage people, and being an artist, I get the opportunity to do the same thing, and spread that love through my work."

Ever since she was little, Cat felt a connection to Lincoln. On her website, she talks about watching, "The face of Lincoln," where sculptor Robert Merrell Gage uses clay to depict Lincoln at different ages. "I was so excited," she says in the video, "that I tore home, I got a chunk of earth, and I carved my own Lincoln."

Fast forward a decade or so, when, after attending school and working as an art director, she decided she wanted to be a stay-at-home mom, but still craved a creative outlet. She was commissioned to paint a portrait, but, was asked if she could create something different for the background. It was then that her signature style was born; grabbing her flat brush she thinned out her paint, and began filling in the space with long, ribbon like strokes. From there, she started experimenting with different tools and subject matter, challenging herself to paint in her new style. Beginning with flowers and clouds, she eventually moved on to figures and faces. Clausen has now painted over 200 Lincolns, among other subjects, after painting the first in 2005 using her unique style.

Fast forward even further, to 2019, at Lake Forest Art Fair, where she would end up connecting with Larry Potash. "I saw her work," Potash says, "and thought it would be an interesting way to bring a contemporary element to a 155 year old story." They would then keep in touch, with Potash sending an email the following fall about the Lincoln program. Always excited to take any opportunity to speak and share her art and love, Clausen agreed, and they arranged to meet at FIBS Brewery, a friend’s beautiful business location, for the taping.

The show Clausen will appear on, "Backstory with Larry Potash," is a show that explores our history, and the stories that connect us to the experiences of those who came before us. Potash gets inspiration for his shows from all kinds of places, most being driven by his own curiosity. "I have learned so much about history doing this show--we all know a tidbit or two about the American Revolution, but doing the research helps put all the random pieces together so you understand the full context," Larry says of Backtory. Through these stories, we get to explore our history outside the simplistic when and where details, journeying instead into the how and why. "I feel Backstory fills a void. The History Channel is full of goofy stories on UFO's and Cults. This is real history, and it's also non-partisan."

Cat’s episode is set to air Saturday, October 10, at 10:30 p.m. "[It starts with] an interview with former presidential advisor Sidney Blumenthal, who is writing a series about Lincoln," explains Potash. "We talk about Lincoln's rise to power, and how nasty politics were then--even more so than now." They also plan to do an additional program on Cat some time next year.

During this first segment, Clausen will be adding finishing touches to various Lincoln paintings, and discussing elements of her unique style as she paints. She chose unfinished pieces as part of the segment partially due to time, but also wanted to be sure to show finished work through larger pieces, so that the audience could still be part of the process. "It just gets more entertaining toward the end," Cat says of the experience. "In the beginning, things are moving kind of slow, and the figure is just starting to take shape...but toward the end, you really get to watch the painting come alive."

Clausen is also currently working on new pieces, including painting a gessoed felt Lincoln top hat with various Lincoln scenes and other related material, inspired by a piece her husband had commissioned from another local artist, Marla Kinkade. She also has several Lincoln related videos and facts on her website, catclausen.net, and continues to add new info for those that share her interest of Lincoln and his influential life. Using art as her platform, she hopes to improve her part of the world, even if just in some small way. This, she says, will always be more important than anything she will make. "[Being an artist isn't necessarily] looking for what to paint, it is simply the personal interaction with others...it's always love."

________________________________________________

Why We Keep Reinventing Abraham Lincoln

From Honest Abe to Killer Lincoln, revisionist biographers have given us countless perspectives on the Civil War President. Is there a version that’s true to his time and attuned to ours?

By Adam Gopnik, September 21, 2020

Lincoln revisionism is not new. In the nineteen-fifties, Edmund Wilson, in these pages, shook off the crooning hagiography of Carl Sandburg’s multivolume biography and replaced it with a vision of Lincoln as a calculating, aggressive nationalist—an American Bismarck, though one in possession of a sternly arresting prose style. The Civil War, in Wilson’s account, was fought for no higher cause than that which makes sea slugs attack other sea slugs: because it is in the nature of beasts to make war. In place of smiling Honest Abe we got lynx-eyed Killer Lincoln.

This view was taken up, with a few complimentary curlicues, in Gore Vidal’s best-selling 1984 novel, "Lincoln." Wilson and Vidal, channelling the ghost of Henry Adams, and seeing themselves as the last redoubts of patrician hauteur, painted their Lincoln against the background of the Cold War. Lincoln’s militarization of the Republic, his invention of an armed national-security state, was taken to be a kind of original sin that would lead to the Pentagon and Vietnam. The lovable Lincoln persisted through this period, but Lincoln was interrogated as much as admired. (And this was merely the revisionism from the left; some Southern conservative intellectuals were still muttering “Sic semper tyrannis.”)

In the decades that followed, the tone of Lincoln biographies became remarkably more benign. There were hymnals in praise of Lincoln’s wisdom in assembling a Cabinet of political opponents (though all Presidents in the era assembled Cabinets of their rivals) and others on the beauty of his language (though Disraeli, in London, was as good a writer in his own way, and no one was deifying him). Spielberg’s Lincoln gave us the beatified, not the Bismarckian, President, even if Daniel Day-Lewis brilliantly caught the high-pitched, less than honeyed tones that Lincoln’s contemporaries heard. In more recent years, however, Lincoln has been under assault—not for being a militarist but for not being militant enough, for not being as thorough an egalitarian as some of the radical Republicans in Congress. Newer Lincoln biographies have been needed, and the need has been met.

David S. Reynolds’s Lincoln is very much an Honest Abe—the title of his book, in fact, is “Abe: Abraham Lincoln in his time” (Penguin Press)—but he is an updated Abe, fully woke and finely radical. Indeed, Reynolds, the author of first-rate biographies of Walt Whitman and John Brown, makes much of Lincoln’s wonderfully named and often forgotten Wide Awakes—legions of young pro-Lincoln “b’hoys,” whose resolve and aggression far exceeded that of Bernie Sanders’s army. Though Reynolds rightly recycles the metaphor of the President as a tightrope walker, we’re assured that, even as the walker might list left and right, his rope stretched forth in a radically progressive direction, aligned with the hot temper of our moment.

Reynolds updates Lincoln by doing what scholars do now: he makes biography secondary to the cultural history of the country. Lincoln is seen as a man whose skin bears the tattoos of his time. Cultural patterns are explicated in “Abe,” and Lincoln is picked up and positioned against them, taking on the coloring of his surroundings, rather like a taxidermied animal being placed in a reconstructed habitat in a nineteenth-century diorama at a natural-history museum. Instead of rising from one episode of strenuous self-making to another, he passes from one frame to the next, a man subsumed.

So, where scholars have long known that Lincoln was plunged into a near-suicidal depression by the early death, in the eighteen-thirties, of his first love, Ann Rutledge, Reynolds connects Lincoln’s depression to a cult of “sensationalism” that swept the country, one that placed great prestige on acts of melodramatic emotion. In Reynolds’s account, Lincoln’s grief was, in part, a literary affect, or even an affectation, with Lincoln and Poe drinking from the same moody waters. This mapping of subject onto trope continues on through the last night of Lincoln’s life. John Wilkes Booth’s assassination of the President, Reynolds argues, was not only an act of terrorism on behalf of the defeated South but a kind of Method-acting exercise gone significantly wrong. Extreme self-identification of actor with role was highly valued then; Junius, the patriarch of the theatrical Booth family, was famed for the hyperintensity of his portrayals, and John, among the three Booth children who became prominent actors, most fully adopted his father’s stormy style. He was pleasing Junius’s ghost by enacting Brutus’s killing of Caesar, in real time with real weapons.

Reynolds’s cultural history illuminates Lincoln—and particularly his transformation from self-made lawyer into American Abe. Even readers long marinated in the Lincoln literature will find revelation in the way “Abe” re-situates familiar episodes. Reynolds places Lincoln’s early career in New Salem and Springfield, Illinois, in the eighteen-thirties, as a poor farm boy struggling to make himself into a middle-class lawyer, against the radical background of American sectarianism. We learn that “free thought” and “free love”—one favoring religious skepticism and the other sex outside marriage—flourished on the frontier, where folks had to make up their own institutions, including a debating club that forbade any appeal to God. Lincoln participated in both movements, declaring himself a freethinker (and apologizing for it in a fairly weaselly way later on, when he first ran for office) and acting as an early advocate for women’s right to vote, and to make their own sexual choices. The young Lincoln was an enthusiastic amateur poet, and his poems are a good guide to one side of his mind: the wild, passionate side, which, Reynolds says, was a counterpart to his youthful calls for “cold, calculating unimpassioned reason.” One poem defended women who’d become prostitutes: “No woman ever played the whore / Without a man to help her.”

Reynolds’s cultural frames become more arresting as Lincoln’s role grows more public; public people are always cultural objects. Lincoln spent February 27, 1860, the day he delivered his Cooper Union speech—the speech that made him President, as he later said—at a hotel across from P. T. Barnum’s museum. Reynolds reflects on Barmun and American Life, and how the love of weird spectacle, what we now call the tabloidization of public people, was something Lincoln welcomed; he played up the comedy of his own appearance in a very Barnum-like way, his enormous body posed against his wife’s petite one. Barnum’s genius lay in taking circus grotesques and making them exemplary Americans: General Tom Thumb was a hero, not a freak. And so with Lincoln, as Reynolds writes: “His cragged face, with its cavernous eyes, large mouth and nose, and swarthy complexion; his wide ears and unruly black hair; his huge hands and feet and overly long arms and legs—these features, along with his ill-fitting clothes and awkward gait, made him seem almost as unusual as a Barnum exhibit.” When Lincoln was President, his Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, compared him to a baboon, and Lincoln, asked how he could endure the insult, said, “That is no insult; it is an expression of opinion; and what troubles me most about it is that Stanton said it, and Stanton is usually right.” He saw that it cost him nothing to be an American spectacle in a climate of American sensation. (He even hosted a reception at the White House for Tom Thumb and his wife.)

Lincoln exploited photography to a similar end, beginning on that same February day, when his portrait was taken at Mathew Brady’s studio. Lincoln was usually pictured not as a polished neoclassical man, like his political rivals, but as rough and frontier-made. Americans like a craggy guy in times of crisis. (Humphrey Bogart offered a similar look in the Second World War.) Even his decision to grow a beard seemed meant to evoke a log-cabin hygiene that was then seen as a sign of sincerity. Lincoln knew how to use the expressive forms of his time as a frame for his mythology. Emerson and Whitman, Reynolds demonstrates, understood Lincoln better, as a national figure, than most journalists could. Emerson saw in him the model self-reliant man and Whitman the ideal democratic leader.

As the war begins, Reynolds’s lens widens in ways that are less appealingly whimsical than in the Barnum case but still more genuinely illuminating. He explains the old puzzle of Lincoln’s reluctance to fire the obstreperous and slow-moving General McClellan as a reflection of Lincoln’s enthusiasm for the new technology of war. Lincoln, a backwoods man forever forward-facing, loved state-of-the-art gizmos, even urging an early machine gun upon the Union Army that it wasn’t willing to use. McClellan shared Lincoln’s vision of an army modernized with telegraph communications, military balloons, and railroad transportation. The choice in 1862 was not yet between McClellan and Grant; it was between McClellan and chaos. The culture of war itself becomes a subject in Reynolds’s book: it explains the eventual turn from McClellan to Grant through a broader mid-nineteenth-century turn from elegant Napoleonic battle orchestrations to Clausewitzian frontal assaults.

Sometimes Reynolds’s kind of cultural history demands more suppleness of mind than he displays. When, for instance, he proposes a parallel between Mary Lincoln locked up in the White House and Emily Dickinson isolated in her home, in Amherst, we feel that we are in the presence of a similitude without a real shape: Emily was a Yankee poet of matchless genius, Mary a bewildered Southern woman in an unmanageable role. All they shared was being alone in a big house. Elsewhere, Reynolds expresses perplexity that the pro-Lincoln satirist David Locke persisted in writing sketches in the voice of Petroleum V. Nasby, his impersonation of a Copperhead—an anti-Lincoln, pro-slavery Northerner. “Given Locke’s actual affection and respect for Lincoln, it must have been very hard for him to maintain the outrageous Copperhead pose,” Reynolds writes. But that’s like wondering why a pro-Biden comedian would keep on impersonating a maga-hat-wearing Trump supporter. Sticking to the joke is what comedians do.

Even with Reynolds’s more compelling examples of anthropological patterns, small whitecaps of uncertainty may stir in the reader’s mind: a man who loses the love of his life does not need cultural license to mourn, and, though Booth undoubtedly choreographed his assassination with an eye to the crowd and to his father, his brothers Junius and Edwin were committed to the manner but appalled by his deed. Actors know overacting when they see it.

Throughout “Abe,” the terms “culture” and “cultural” recur with such hammering relentlessness (four times on a single page, and in that chapter title as well) that one wishes Reynolds’s editor had given him a thesaurus. Not having enough words means not seeing enough types. Culture is a diffuse thing. Reading a book, choosing a costume, adapting a rhetorical style, transferring a code of conduct from one forum to another, just laughing at a joke—each of these forms of cultural transmission has its own vibration, its own dynamic, and its own web of associations.

What counts is a sense of what counts. It’s true that, as Reynolds shows in his account of sensationalism, Lincoln loved sad parlor songs, but pretty much everyone in the period loved sad songs; to make much of this is like making the possession of an e-mail address a significant cultural token today. On the other hand, although the Shakespeare whom Lincoln loved was very much the Shakespeare beloved by nineteenth-century America—a strenuous moralist, devoted to the explication of characters in extreme emotional states—Lincoln was distinctive in turning this shared Shakespeare into a template for a new kind of oratory. The passionate phrasing and sharp summations of Lincoln’s speeches—“the better angels of our nature”; “of the people, by the people, for the people”—are shaped by the passionate soliloquies and monosyllabic end stops of Shakespeare’s most agonized characters. (Among Lincoln’s favorite passages was Claudius’s guilt-ridden “Oh, my offense is rank” speech.) The interpenetration of Abe and Will is real. It is important to recognize cultural set pieces, but it’s also important to see that they are malleable and self-created. Lincoln made his time as much as he lived in it. That, after all, is why we’re reading this book.

Macro-history gives us a big picture, but politics, as "Hamilton" reminds us, happens in hidden rooms. Readers who seek the political micro-history can turn to Sidney Blumenthal’s multivolume Lincoln biography, now in its third installment—“All The Powers Of The Earth” (Simon & Schuster)—with two more promised. Written by someone who bears the battle scars of modern democratic politics, the volumes are all about Lincoln as a battle-scarred democratic politician. (Blumenthal, who was once a staff writer for this magazine, worked as an adviser to President Clinton and distinguished himself in the Ken Starr wars.) Where Reynolds’s account of the most significant act in American political history—Lincoln’s insurgent victory over William Seward, a senator from New York, in the Republican-nomination battle of 1860—is necessarily summary, Blumenthal offers a vividly realized, slow crawl across the Convention floor by someone who has been there.

The heroes of Blumenthal’s most recent volume are the so-called Lincoln Men, a group of boosters and advisers led by David Davis and Leonard Swett, who, with a comic brio right out of Mark Twain, employed every hardball trick in the book to win Lincoln the nomination. At the Wigwam, in Chicago—an immense wooden convention hall, capable of holding more than ten thousand people, and thrown together, American style, in a month—they boxed out the Seward forces, making it physically difficult for his delegates to mingle and make deals.

The Lincolnians also courted a now often overlooked interest group, the émigré Germans, including many exiled by the failed liberal revolutions of 1848. As Blumenthal notes, Lincoln had bought a German-language newspaper, in order to appeal to those key players of the “identity politics” of the time. (It was the equivalent of surreptitiously funding Facebook pages in 2020.) The Germans refused to support anyone who was known to have a pro-nativist taint, which ruled out a lot of dog-eared veteran politicians. At the same time, the nativists spurned Seward, who, as governor of New York, had backed state subsidies for Catholic education. In the end, it all came down to a single eve-of-battle meeting in Chicago between the Lincoln Men and a group of delegates from Pennsylvania, who proposed a flat-out political swap: they’d support Lincoln in exchange for a Cabinet post going to Simon Cameron, a corrupt Pennsylvania senator. David Davis agreed. Lincoln had officially warned him off such dealmaking, but, as he memorably said, “Lincoln ain’t here.” (Lincoln gave Cameron the War Office, not the Department of Treasury he wanted; Davis, for his efforts, got a seat on the Supreme Court.)

As with Kennedy in 1960 and the Obama campaign in 2008, a macro-moment met micromanagement. The background in each case was the elevation of a novice with a gift for speaking, an extraordinary personal story, and a political record too short to have incurred too many grudges. The foreground was sharp dealing. Blumenthal’s kind of intricate political history—providing all the details of how the sprockets and gears engage—feeds, in turn, the larger cultural perspective. It’s hard to grasp, today, the extent to which those émigré Germans were perceived as the soul of the educated élite. (In Louisa May Alcott's, “Little Women” series, it is the idealized German—and perhaps Jewish—Professor Bhaer, with his heavy accent and love of Goethe, who rescues Jo from conventionality and joins her in building a progressive school.) It may be an obvious truth, but it is still a truth worth telling: history needs both micro-political and macro-cultural perspectives. The room where it happened is part of a world where it could.

Reynolds’s macro-history and Blumenthal’s micro-history coincide in their vindication of Lincoln as a profound radical. Lincoln was a single-issue candidate and a single-cause politician; that issue was slavery and the cause was its abolition. But he was a politician, not a polemicist: he created a broad coalition and placated its parts. He was a pluralist rather than a purist.

His central understanding, registered in his home base of Springfield—where, Reynolds shows, there was a lot more African-American political activism than has often been imagined—was that racist Northerners who could not be driven to equality could still be coaxed toward humanity. Abolition annealed to a broader “Americanism”—an understanding of equality as rooted in the sacred documents of the country—might produce emancipation. This was an insight that Lincoln, with Machiavellian shrewdness, drove to an armed point. Lincoln was not a centrist politician who happened to find himself on top of an erupting volcano in 1861; his election caused the eruption. As Blumenthal shows, Lincoln, in his 1858 debates with the racist senator Stephen Douglas, tactically conceded points about segregation: “I do not understand that because I do not want a negro woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife.” But he was emphatic on the central point, that “there is no reason in the world why the negro is not entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence—the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. I hold that he is as much entitled to these as the white man.”

In a speech in Peoria, Lincoln declared, about the indifference toward slavery he saw in Congress, “I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world . . . and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty.” Reynolds, quoting this passage, remarks that “Lincoln’s loathing of slavery comes through as strongly here as it does in any work by the most radical abolitionist.” What separated Lincoln from most other abolitionists was the absence of rhetoric that was intended to frighten as much as teach—what Reynolds calls “dark reform” rhetoric—or that catalogued, graphically but accurately, the physical horrors inflicted by slave masters.

This wasn’t because Lincoln did not know of these horrors. It was because he understood that moving the masses of the North to abolition could be done only by appealing to fundamental principles—reminding them that their own values were being violated, not merely another group’s interests. Reynolds writes that Lincoln, aware of the risks of the kind of nihilistic bloodletting that John Brown would produce, directed “this potentially anarchistic cultural current into two documents treasured by most Americans: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.” By linking the fight against slavery to the extension of these documents, rather than to their repudiation, he could build a truly broad antislavery coalition—and an army brutal enough to enforce its mission. Every act of his Presidency, from the gathering of the militias to the speech at Gettysburg, moved toward this end.

It worked, at a price. For Lincoln, the critical issue was the abolition of slavery; racism and its constraints were, for the moment, secondary. Reynolds addresses Lincoln’s supposed racism in considering colonization programs for freed slaves, noting that Martin Delany, the most radical Black activist of the time, had also championed relocating Black people away from the degradations they faced here. It was a back-to-Africa sentiment, a kind of Black Zionism, that both Lincoln and Delany contemplated. Similarly, Lincoln’s notorious letter to the New York newspaper editor Horace Greeley, saying that if he could save the Union without freeing any slaves he would do so, is situated as part of an ongoing joust between Lincoln and Greeley—and, Reynolds says, as a way for Lincoln to garb “his radical antislavery position in the dress of military necessity.”

An unexampled source on the subject of Lincoln at war—what it cost him and what he really believed—remains John Stauffer’s “Giants,” a 2008 study of Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. And the best summation of Lincoln is still the oration delivered by Douglass in 1876 on the unveiling of a monument to the freed slaves:

Despite the mist and haze that surrounded him; despite the tumult, the hurry, and confusion of the hour, we were able to take a comprehensive view of Abraham Lincoln, and to make reasonable allowance for the circumstances of his position. We saw him, measured him, and estimated him; not by stray utterances to injudicious and tedious delegations, who often tried his patience; not by isolated facts torn from their connection; not by any partial and imperfect glimpses, caught at inopportune moments; but by a broad survey, in the light of the stern logic of great events, and in view of that divinity which shapes our ends, rough hew them how we will, we came to the conclusion that the hour and the man of our redemption had somehow met in the person of Abraham Lincoln.

Sometimes cultural works, novels and plays, can tell you more about the history of culture than cultural history can. George Saunders’s universally praised novel “Lincoln in the Bardo” (2017) creates an imagined Lincoln for our era that more literal accounts can only reinforce and echo. Saunders’s novel, an oratorio of fragments sung by American ghosts huddled in a graveyard, crowding around (and, creepily, inside) Lincoln himself as he mourns his son Willie, who died in 1862, makes that death the center point of Lincoln’s journey.

Reynolds, in turn, reveals that Spiritualism—hard-core, table-rapping Spiritualism—really was a presence in the Lincoln White House. The movement, as American as Mormonism, had begun in the eighteen-forties with the Fox sisters and their pet ghost, Mr. Splitfoot, and by the eighteen-seventies had millions of adherents. Poor Mary Lincoln, after losing Willie, consulted Spiritualists who claimed to commune with the dead, and held séances in the White House, which her husband seems to have attended. Abe himself took seriously the political counsel he got from two leading spirit-mongers, though not from their spirits.

However clearly stage-managed, this cult of an accessible afterlife gave to the tragedies of the war a set of redemptive possibilities that normal religiosity couldn’t quite contain, and adds to our understanding of Civil War mourning. Reynolds even includes a hair-raising, and heartbreaking, “spirit” photograph of Mary Lincoln with Abe’s ghost, contrived for her years after his death. The obviousness of the fraud does not alter the pathos of the embrace, the tall man’s hands placed on the small woman’s shoulders. The phony and freakish treated as heroic and elegiac—these elements, the materials of Melville’s “The Confidence-Man,” are the materials of mid-nineteenth-century American culture. Lincoln’s legend sits right there among them.

Saunders’s ghosts include those of soldiers killed in the war, reproaching the President as he mourns his own child. There is a terrible Providence in the Lincolns’ undergoing the same kind of loss that so many less celebrated Americans had to endure. The ghosts did indeed live alongside the living. Surely the belief in ghosts was, in part, a way of registering the mass killing of ordinary boys—and their persistence as a constant harrowing of the soul. All wars leave a hideous deficit, but the Civil War somehow left one uniquely deep. To grasp why the comedy of séance-table Spiritualism was not comedy at all, one must reckon with the scale of the killing—proportionally, it is as if eight million Americans were killed in a war now. And, perhaps, above all, one must reckon with the adjacency, the nearness of the places where these farm boys and working men with wives and babies were slaughtered to the places where they had lived: they died not in a foreign glade or on a distant shore but in a hayfield across the state border.

Lincoln was a pluralist politician negotiating a world resistant to pluralism of any kind. He achieved great things through compromise and cunning and occasional cruelty. The choice between pluralism and purism remains the defining choice between liberalism and its enemies. It is why, astoundingly, John Wilkes Booth adored John Brown. They spoke the same language of absolutism.

With the recent degradation of the American Presidency—our four-year nightmare has provided no spectacle more nightmarish than that of Trump sitting at Lincoln’s feet, in his memorial, for a self-pity session—it is a truism to say that we need Lincoln again. But which one? Three possible Lincolns come to mind. Call them a Barnum Lincoln, a Bardo Lincoln, and a Wigwam Lincoln.

The Barnum Lincoln shows us that a vigorous thread of vulgarity ran right through Lincoln’s life and public persona, and appropriately so for a democratic leader. Though not a vulgarian himself, Lincoln saw the value of vulgarity. The sepulchral Lincoln of Daniel French’s statue was not the Lincoln his contemporaries knew and loved. One of the actors in “Our American Cousin,” seeing the First Couple arrive in their box not long before the President was killed, ad-libbed the line “This reminds me of a story, as Mr. Lincoln says . . . ,” to great and appreciative laughter. This was the Lincoln his time knew: ribald storyteller, fabulist, beloved Barnum-style freak. It is a Lincoln worth keeping in mind for those of us inclined to bemoan the “debasement” of our political culture. (The trouble with Trump is not that he’s a short-fingered vulgarian showman; the trouble is that he is only a short-fingered vulgarian showman.)

It is the Bardo Lincoln who radiates moral authority from his time into our own, exactly because he was one of those rare leaders who could stare directly into their complicity in death and suffering without attempting to weaken or lessen its horror. Lincoln was in intimate touch with the suffering he made happen, and he sought every day to justify it, to himself and to the country. He sensed from very early on that he would never go home to Illinois; the spectre of assassination was constant throughout his Presidency, and his legendary dream of death in the White House is a sign that he accepted this. The British philosopher and Lincoln lover John Stuart Mill wrote soon after the President’s death that there was something almost salubrious in his dying just as the war was won. Shocking as it sounds, Mill meant that, in some almost providential way, the arc of Lincoln’s life demanded his martyrdom to complete it. This Lincoln, the man of sorrows acquainted with grief, is central to understanding the spell he continues to cast on us.

If there’s a Lincoln we need now, though, it must be the Wigwam Lincoln, the pol who pretended to oppose dealmaking in the boozy Chicago night, even as his ambition demanded it. That’s the ghost to haunt us—master politician, always placating one side in order to broaden a path to another, misdirecting and redirecting, building and rebuilding coalitions, all of it guided by shrewd insight into other people’s foibles and needs. What really distinguished Lincoln from the other Presidents who built Cabinets of rivals was that, instead of struggling against them politely, he played them like a piano. He expected to lose the election of 1864, and hatched an apparent plot—involving a secret letter that he demanded his Cabinet sign, unseen—to get as many slaves freed as possible if he did. (And then the election of 1864 was duly held, in the middle of a war, with millions of voters, and no one has ever had cause to question its legitimacy.) Lincoln will not return from the dead, even as a ghost, but his broadly balanced, extravagantly compromised democratic pluralism may be all there is to rescue us yet again. Something has to, soon.

_____________________________________________________

"Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish. And the war came."

--A. Lincoln in his second inaugural address, March 4, 1865

March 4, 1865, arrived in the national capitol cold, wet and dreary. Because most Washington streets were unpaved, people slogged through a sea of mud to watch Abraham Lincoln take his second oath of office as the president of the United States. His amazing speech at Gettysburg notwithstanding, many people had yet to discover the depth of Lincoln's ability to frame a complex issue simply and succinctly. Still, others knew well his deserved reputation as an orator. These people expected Lincoln would use the occasion of his second inaugural ceremony to address the anticipated end of the war and how he would treat the defeated Southern states. He did not disappoint them.

The Inaugural formalities took place outdoors in front of the Capitol, where former Treasury Secretary (now Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court) Salmon P. Chase swore in Lincoln and Lincoln gave his speech. And what a speech it was! In just over 700 words, Lincoln reiterated the reason both sides went to war, summarized the sacrifices made to preserve the nation as a whole, and clarified his position on how the nation should proceed once the last shot had been fired, In a moment made for television, Lincoln stepped to the podium to give his speech, and the rain stopped. The clouds parted, and a dove flew above the crowd. Then, in his high-pitched voice, Abraham Lincoln delivered the last great speech of his life.

He invoked

God He mentioned the Bible. He promised to take any measure that would not just preserve the Union but eradicate slavery, even if, as he said, "God wills that (the war) continue, until all the wealth piled by the bondman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood draw with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword."

As with all of his great speeches, Lincoln's second inaugural address concluded on an inspirational, invocatory note:

"With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan--to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations."

Lincoln made a point of not differentiating between Northern and Southern veterans or their widows or orphans in calling on the nation to help heal the wounds inflicted by the devastating war. Despite the loud protests of Radical Republicans in Congress, he wanted to be lenient with returning Southern states. He enunciated this desire shortly before his death, when he said that his main concern in concluding the war was "to get the men composing the Confederate armies back to their homes, at work on their farms or in their shops."

It is entirely possible that Lincoln might have succeeded in carrying out his reconstruction program of the Southern states, had he lived much past the end of the war. As it happened, Lincoln was dead within weeks of Lee's final surrender at Appomattox Courthouse in April 1865, and his successor, Andres Johnson, although disposed by his Tennessee roots to deal lightly with the South, did not possess the requisite political skill to do so while also handling the Republican Congress. The result was not Lincoln's hoped-for quick recovery from four years of bloody civil war, but military occupation, a power struggle in the highest reaches of the federal government, and the eventual first impeachment of a sitting president of the United States. All of these things probably wouldn't have happened had Abraham Lincoln lived to serve out the second term that began so promisingly on that rainy March day when the sun unexpectedly came out at just the right moment, and when hopes were high.

_____________________________________________________________________

That was Lincoln's best speech and why isn't there a transcript --?

Is it the Gettysburg Address --? No. The second inaugural --? Nuh-uh. The "house divided" speech he gave during the 1858 Illinois senatorial race --? Apparently not. According to none other than Lincoln's own law partner William H. Herndon, Abraham Lincoln gave the speech of his life not at the dedication of the Gettysburg National Cemetery, not in Washington, D.C., on the occasion of his second inauguration as president, not during a senate race, but in Bloomington, Illinois, in 1856.

It went something like this: In 1856, the new Republican Party was still feeling its way around organizationally. As with any new organization, a bureaucracy needs to be set up and tasks must be identified and delegated. So from 1854 to 1856, the Republican Party sponsored a series of grass-root-level organizational meetings to accomplish these sorts of goals.

One of these meetings took place on May 29, 1856, at Major's Hall. By this time, Herndon had acquired the habit of taking notes on his partner's speeches. Over forty reporters attended, and yet no complete record of the speech Lincoln gave to the delegates assembled there remains.

Lincoln's importance in the new Republican party dictated that he give the last speech of the evening. By all accounts, it was a whopper. As Herndon later explained, he "attempted for about fifteen minutes, as was usual with me then to take notes, but at the end of that time I threw pen and paper away and lived only in the inspiration of the hour." Of all the members of the press in attendance, only one, the correspondent sent by the Alton Weekly Courier, gave anything resembling a summary of Lincoln's address. According to the article the Weekly Courier later published, Lincoln laid out "the pressing reasons of the present moment, "then went on to attack slavery as the root of the nation's many woes. In a break with his earlier position refusing to overtly target slavery or slaveholders. Lincoln condemned Southerners for attempting to paint slavery as not only positive in the lives of black slaves, but a potential solution to the problems suffered by many Northern laborers.

From there, he went on to decry Illinois senator Stephen A. Douglas and the other Northern Democrats, claiming they too accepted the argument that slavery must be extended throughout the country. (He was wrong on this point. Douglas and the Northern wing of the party he led were trying to walk a razor's edge of compromise to forestall a split in the party's ranks, and they never did accept the argument.) According to Lincoln, the answer was for antislavery forces to put aside their differences. Conservative Whigs and anti-immigrant Know Nothings, Democrats who had broken with their former party over the question of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, radical abolitionists--they all needed to come together under the banner of the Republican Party to combat the encroachment of slavery into the North.

It was a rousing speech, and the ending was particularly effective. If Southerners responded to Northern attempts to halt slavery's encroachment by raising "the bugbear of disunion," Lincoln said, then the united opponents of slavery in the North must drive home forcefully to their countrymen in the South that "the Union must be preserved in the purity of its principles as well as in the integrity of its territorial parts." Lincoln would later echo this sentiment while retreating publicly from the notion that slavery was inconsistent with democratic principles by saying to Horace Greeley that as president his job was to preserve the Union, not to free the slaves. And yet before he was finished, he did both.

"His speech was full of fire and energy and force." Herndon later wrote. It "was logic; it was pathos; it was enthusiasm; it was justice, equality, truth, and right set ablaze by the divine fires of a soul maddened by the wrong; it was hard, heavy, knotty, gnarly, backed with wrath."

It was Abraham Lincoln.

______________________________________

The Battle of the Wilderness

The Battle of the Wilderness, fought May 5–7, 1864, was the first battle of Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's and General George G. Meade's 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against Gen. Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War. Both armies suffered heavy casualties, around 5,000 men killed in total, a harbinger of a bloody war of attrition by Grant against Lee's army and, eventually, the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia. The battle was tactically inconclusive, as Grant disengaged and continued his offensive.

Grant attempted to move quickly through the dense underbrush of the Wilderness of Spotsylvania, but Lee launched two of his corps on parallel roads to intercept him. On the morning of May 5, the Union V Corps under Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren attacked the Confederate Second Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, on the Orange Turnpike. That afternoon the Third Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill, encountered Brig. Gen. George W. Getty's division (VI Corps) and Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock's II Corps on the Orange Plank Road. Fighting until dark was fierce but inconclusive as both sides attempted to maneuver in the dense woods.

At dawn on May 6, 1864, Hancock attacked along the Plank Road, driving Hill's Corps back in confusion, but the First Corps of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet arrived in time to prevent the collapse of the Confederate right flank. Longstreet followed up with a surprise flanking attack from an unfinished railroad bed that drove Hancock's men back to the Brock Road, but the momentum was lost when Longstreet was wounded by his own men. An evening attack by Brig. Gen. John B. Gordon against the Union right flank caused consternation at Union headquarters, but the lines stabilized and fighting ceased. On May 7, Grant disengaged and moved to the southeast, intending to leave the Wilderness to interpose his army between Lee and Richmond, leading to the bloody Battle of Spotsylvania Court House.

In March 1864, Grant was summoned from the Western Theater, promoted to lieutenant general, and given command of all Union armies. He chose to make his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac, although Meade retained formal command of that army. Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman succeeded Grant in command of most of the western armies. Grant, President Abraham Lincoln, and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the heart of the Confederacy from multiple directions, including attacks against Lee near Richmond, Virginia, and in the Shenandoah Valley, West Virginia, Georgia, and Mobile, Alabama. This was the first time the Union armies would have a coordinated offensive strategy across a number of theaters.

On April 27, 1864, a dispatch was sent by P. H. Sheridan to Maj. Gen. Humphreys, Chf. Of Staff, Headquarters Cavalry Corps to forward the following message from Brig. Gen. D. McM. Gregg: Col. Taylor at Morrisville reports all quiet in that section. He forwards a report from Commanding officer at Grove Church that he learned from citizens who have taken the oath that there were 6,000 Rebel Cavalry at Fredericksburg on the 26th, that Longstreet’s force is at Gordonsville. Col. Taylor asks permission to send 100 men on a scout to Falmouth to obtain information.

Grant's campaign objective was not the Confederate capital of Richmond, but the destruction of Lee's army. Lincoln had long advocated this strategy for his generals, recognizing that the city would certainly fall after the loss of its principal defensive army. Grant ordered Meade, "Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also."[11] Although he hoped for a quick, decisive battle, Grant was prepared to fight a war of attrition. Both Union and Confederate casualties could be high, but the Union had greater resources to replace lost soldiers and equipment.

On May 4, 1864, the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River at three separate points and converged on the Wilderness Tavern, near the edge of the Wilderness of Spotsylvania, an area of more than 70 sq mi (181 km) of Spotsylvania County and Orange County in central Virginia. Early settlers in the area had cut down the native forests to fuel blast furnaces that processed the iron ore found there, leaving what was mainly a secondary growth of dense shrubs. This rough terrain, which was virtually unsettled, was nearly impenetrable to 19th-century infantry and artillery maneuvers. A number of battles were fought in the vicinity between 1862 and 1864, including the bloody Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863.

The Wilderness had been the concentration point for the Confederates one year earlier when Stonewall Jackson launched his devastating attack on the Union right flank at Chancellorsville. But Grant chose to set up his camps to the west of the old battle site before moving southward; unlike the Union army of a year before, Grant had no desire to fight in the Wilderness, preferring to move to the open ground to the south and east of the Wilderness before fighting Lee, thereby taking advantage of his superior numbers and artillery.

Grant's plan was for the V Corps (Warren) and VI Corps (Sedgwick) to cross the Rapidan at Germanna Ford, followed by the IX Corps (Burnside) after the supply trains had crossed at various fords, and to camp near Wilderness Tavern. The II Corps (Hancock) would cross to the east on Ely's Ford and advance to Spotsylvania Court House by way of Chancellorsville and Todd's Tavern. Speed was of the essence to the plan because the army was vulnerably stretched thin as it moved. Although Grant insisted that the army travel light with minimal artillery and supplies, its logistical "tail" was almost 70 miles.

Sylvanus Cadwallader, a journalist with the Army of the Potomac, estimated that Meade's supply trains alone—which included 4,300 wagons, 835 ambulances, and a herd of cattle for slaughter—if using a single road would reach from the Rapidan to below Richmond. Grant gambled that Meade could move his army quickly enough to avoid being ensnared in the Wilderness, but Meade recommended that they camp overnight to allow the wagon train to catch up. Grant also miscalculated when he assumed that Lee was incapable of intercepting the Union army at its most vulnerable point, and Meade had not provided adequate cavalry coverage to warn of a Confederate movement from the west.

On May 2, 1864, Lee met with his generals on Clark Mountain, obtaining a panoramic view of the enemy camps. He realized that Grant was getting ready to attack, but did not know the precise route of advance. He correctly predicted that Grant would cross to the east of the Confederate fortifications on the Rapidan, using the Germanna and Ely Fords, but he could not be certain. To retain flexibility of response, Lee had dispersed his Army over a wide area. Longstreet's First Corps was around Gordonsville, from where they had the flexibility to respond by railroad to potential threats to the Shenandoah Valley or to Richmond. Lee's headquarters and Hill's Third Corps were outside Orange Court House. Ewell's Second Corps was the closest to the Wilderness, at Morton's Ford.

As Grant's plan became clear to Lee on May 4, Lee knew that it was imperative to fight in the Wilderness for the same reason as the year before: his army was massively outnumbered, with approximately 65,000 men to Grant's 120,000, and his artillery's guns were fewer than and inferior to those of Grant's. Fighting in the tangled woods would eliminate Grant's advantage in artillery, and the close quarters and ensuing confusion there could give Lee's outnumbered force better odds. He therefore ordered his army to intercept the advancing Federals in the Wilderness.

Ewell marched east on the Orange Court House Turnpike, reaching Robertson's Tavern, where they camped about 3–5 miles from the unsuspecting soldiers in Warren's corps. Hill used the Orange Plank Road and stopped at the hamlet of New Verdiersville. These two corps could pin the Union troops in place (they had been ordered to avoid a general engagement until the entire army could be united), fighting outnumbered for at least a day while Longstreet approached from the southwest for a blow against the enemy's flank, similar to Jackson's at Chancellorsville.

The thick underbrush prevented the Union Army from recognizing the proximity of the Confederates. Adding to the confusion, Meade received an erroneous report that the Confederate cavalry under J.E.B. Stuart was operating in his Army's rear, in the direction of Fredericksburg. He ordered the bulk of his cavalry to move east to deal with that perceived threat, leaving his army blind. But he assumed that the corps of Sedgwick, Warren, and Hancock could hold back any potential Confederate advance until the supply trains came up, at which time Grant could move forward to engage in a major battle with Lee, presumably at Mine Run.

Early on May 5, Warren's V Corps was advancing over farm lanes toward the Plank Road when Ewell's Corps appeared in the west. Grant was notified of the encounter and instructed, "If any opportunity presents itself of pitching into a part of Lee's army, do so without giving time for disposition." Meade halted his army and directed Warren to attack, assuming that the Confederates were a small, isolated group and not an entire infantry corps. Ewell's men erected earthworks on the western end of the clearing known as Saunders Field.

Warren approached on the eastern end with the division of Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin on the right and the division of Brig. Gen. James S. Wadsworth on the left, but he hesitated to attack because the Confederate position extended beyond Griffin's right, which would mean that they would be subjected to enfilade fire. He requested a delay from Meade so that Sedgwick's VI Corps could be brought in on his right and extend his line. By 1 p.m., Meade was frustrated by the delay and ordered Warren to attack before Sedgwick could arrive.

Warren was correct to be concerned about his right flank. As the Union men advanced, Brig. Gen. Romeyn B. Ayres's brigade had to take cover in a gully to avoid the enfilading fire. The brigade of Brig. Gen. Joseph J. Bartlett made better progress to Ayres's left and overran the position of Brig. Gen. John M. Jones, who was killed. However, since Ayres's men were unable to advance, Bartlett's right flank was now exposed to attack and his brigade was forced to flee back across the clearing. Bartlett's horse was shot out from under him and he barely escaped capture.

To the left of Bartlett, the Iron Brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Lysander Cutler, advanced through woods south of the field and struck a brigade of Alabamians commanded by Brig. Gen. Cullen A. Battle. Although initially pushed back, the Confederates counterattacked with the brigade of Brig. Gen. John B. Gordon, tearing through the line and forcing the Iron Brigade (now filled with green recruits from its devastating losses at Gettysburg) to break for the first time in its history. As the majority of the new recruits fled from the terrors of combat, the old veterans of the brigade attempted to hold their ground and eventually were forced to retreat against overwhelming odds.

Further to the left, near the Higgerson farm, the brigades of Col. Roy Stone and Brig. Gen. James C. Rice attacked the brigades of Brig. Gen. George P. Doles's Georgians and Brig. Gen. Junius Daniel's North Carolinians. Both attacks failed under heavy fire and Crawford ordered his men to pull back. Warren ordered an artillery section into Saunders Field to support his attack, but it was captured by Confederate soldiers, who were pinned down and prevented by rifle fire from moving the guns until darkness. In the midst of hand-to-hand combat at the guns, the field caught fire and men from both sides were shocked as their wounded comrades burned to death.

The lead elements of Sedgwick's VI Corps reached Saunders Field at 3 p.m., by which time Warren's men had ceased fighting. Sedgwick attacked Ewell's line in the woods north of the Turnpike and both sides traded attacks and counterattacks that lasted about an hour before each disengaged to erect earthworks. During the fray, Confederate Brig. Gen. Leroy A. Stafford was shot through the shoulder blade, the bullet severing his spine. Despite being paralyzed from the waist down and in agonizing pain, he managed to still urge his troops forward.

May 5: Unable to duplicate the surprise that was achieved by Ewell on the Turnpike, A.P. Hill's approach was detected by Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Crawford's men from their position at the Chewning farm, and Meade ordered the VI Corps division of Brig. Gen. George W. Getty to defend the important intersection of the Orange Plank Road and the Brock Road. Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson, employing repeating carbines, succeeded in briefly delaying Hill's approach. Getty's men arrived just before Hill's and the two forces skirmished briefly, ending with Hill's men withdrawing a few hundred yards west of the intersection.

Much of the fighting near Orange Plank Road was in close quarters and the thicket along the road, accompanied with the smoke from rifles, caused much confusion amongst officers of both sides. A mile to the rear, Lee established his headquarters at the Widow Tapp's farm. Lee, Jeb Stuart, and Hill were meeting there when they were surprised by a party of Union soldiers entering the clearing. The three generals ran for safety and the Union men, who were equally surprised by the encounter, returned to the woods, unaware of how close they had come to changing the course of history. Meade sent orders to Hancock directing him to move his II Corps north to come to Getty's assistance.

By 4 p.m., initial elements of Hancock's corps were arriving and Meade ordered Getty to assault the Confederate line. As the Union men approached the position of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth, they were pinned down by fire from a shallow ridge to their front. As each II Corps division arrived, Hancock sent it forward to assist, bringing enough combat power to bear that Lee was forced to commit his reserves, the division commanded by Maj. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox. Fierce fighting continued until nightfall with neither side gaining an advantage.

Plans for May 6: Grant's plan for the following day assumed that Hill's Corps was essentially spent and was a prime target. He ordered an early morning assault down the Orange Plank Road by the II Corps and Getty's division. At the same time, the V and VI Corps were to resume assaults against Ewell's position on the Turnpike, preventing him from coming to Hill's aid, and Burnside's IX Corps was to move through the area between the Turnpike and the Plank Road and get into Hill's rear. If successful, Hill's Corps would be destroyed and then the full weight of the army could follow up and deal with Ewell's.

Although he was aware of the precarious situation on the Plank Road, rather than reorganizing his line, Lee chose to allow Hill's men to rest, assuming that Longstreet's Corps, now only 10 miles from the battlefield, would arrive in time to reinforce Hill before dawn. When that occurred, he planned to shift Hill to the left to cover some of the open ground between his divided forces. Longstreet calculated that he had sufficient time to allow his men, tired from marching all day, to rest and the First Corps did not resume marching until after midnight. Moving cross-country in the dark, they made slow progress and lost their way at times, and by sunrise had not reached their designated position.

Actions in the Wilderness, May 6: As planned, Hancock's II Corps attacked Hill at 5 a.m., overwhelming the Third Corps with the divisions of Wadsworth, Birney, and Mott; Getty and Gibbon were in support. Ewell's men on the Turnpike had actually attacked first, at 4:45 a.m., but continued to be pinned down by attacks from Sedgwick's and Warren's corps and could not be relied upon for assistance. Lt. Col. William T. Poague's 16 guns at the Widow Tapp farm fired canister tirelessly, but could not stem the tide and Confederate soldiers streamed toward the rear. Before a total collapse, however, reinforcements arrived at 6 a.m., Brig. Gen. John Gregg's 800-man Texas Brigade, the vanguard of Longstreet's column. General Lee, relieved and excited, waved his hat over his head and shouted, "Texans always move them!" Caught up in the excitement, Lee began to move forward with the advancing brigade. As the Texans realized this, they halted and grabbed the reins of Lee's horse, Traveller, telling the general that they were concerned for his safety and would only go forward if he moved to a less exposed location. Longstreet was able to convince Lee that he had matters well in hand and the commanding general relented.

Confederate troops capture part of the Union breastworks near the Brock Road Longstreet counterattacked with the divisions of Maj. Gen. Charles W. Field on the left and Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw on the right. The Union troops, somewhat disorganized from their assault earlier that morning, could not resist and fell back a few hundred yards from the Widow Tapp farm. The Texans leading the charge north of the road fought gallantly at a heavy price—only 250 of the 800 men emerged unscathed. At 10 a.m., Longstreet's chief engineer reported that he had explored an unfinished railroad bed south of the Plank Road and that it offered easy access to the Union left flank. Longstreet assigned his aide, Lt. Col. Moxley Sorrel, to the task of leading four fresh brigades along the railroad bed for a surprise attack. Sorrel and the senior brigade commander, Brig. Gen. William Mahone, struck at 11 a.m. Hancock wrote later that the flanking attack rolled up his line "like a wet blanket." At the same time, Longstreet resumed his main attack, driving Hancock's men back to the Brock Road, and mortally wounding Brig. Gen. James S. Wadsworth.

Longstreet rode forward on the Plank Road with several of his officers and encountered some of Mahone's men returning from their successful attack. The Virginians believed the mounted party were Federals and opened fire, wounding Longstreet severely in his neck and killing a brigade commander, Brig. Gen. Micah Jenkins. Longstreet was able to turn over his command directly to Charles Field and told him to "Press the enemy." However, the Confederate line fell into confusion and before a vigorous new assault could be organized, Hancock's line had stabilized behind earthworks at the Brock Road. The following day, Lee appointed Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson to temporary command of the First Corps. Longstreet did not return to the Army of Northern Virginia until October 13. (By coincidence, he was accidentally shot by his own men only about 4 miles (6.4 km) away from the place where Stonewall Jackson suffered the same fate a year earlier.)

Actions in the Wilderness on May 6 are as follows. Longstreet attacks Hancock's flank from the railroad bed. Gordon's attacks, 2 p.m. until dark. At the Turnpike, inconclusive fighting proceeded for most of the day. Early in the morning, Brig. Gen. John B. Gordon scouted the Union line and recommended to his division commander, Jubal Early, that he conduct a flanking attack, but Early dismissed the venture as too risky. According to Gordon's account after the war, General Lee visited Ewell and ordered him to approve Gordon's plan, but other sources discount Lee's personal intervention. In any event, Ewell authorized him to go ahead shortly before dark. Gordon's attack made good progress against inexperienced New York troops who had spent the war up until this time manning the artillery defenses of Washington, D.C., but eventually the darkness and the dense foliage took their toll as the Union flank received reinforcements and recovered. Sedgwick's line was extended overnight to the Germanna Plank Road. For years after the war, Gordon complained about the delay in approving his attack, claiming "the greatest opportunity ever presented to Lee's army was permitted to pass."

Reports of the collapse of this part of the Union line caused great consternation at Grant's headquarters, leading to an interchange that is widely quoted in Grant biographies. An officer accosted Grant, proclaiming, "General Grant, this is a crisis that cannot be looked upon too seriously. I know Lee's methods well by past experience; he will throw his whole army between us and the Rapidan, and cut us off completely from our communications." Grant seemed to be waiting for such an opportunity and snapped, "Oh, I am heartily tired of hearing about what Lee is going to do. Some of you always seem to think he is suddenly going to turn a double somersault, and land in our rear and on both of our flanks at the same time. Go back to your command, and try to think what we are going to do ourselves, instead of what Lee is going to do."

On the morning of May 7, Grant was faced with the prospect of attacking strong Confederate earthworks. Instead, he chose maneuver. By moving south on the Brock Road, he hoped to reach the crossroads at Spotsylvania Court House, which would interpose his army between Lee and Richmond, forcing Lee to fight on ground more advantageous to the Union army. He ordered preparations for a night march on May 7 that would reach Spotsylvania, 10 mi (16 km) to the southeast, by the morning of May 8. Unfortunately for Grant, inadequate cavalry screening and bad luck allowed Lee's army to reach the crossroads before sufficient Union troops arrived to contest it. Once again faced with formidable earthworks, Grant fought the bloody Battle of Spotsylvania Court House (May 8–21) before maneuvering yet again as the campaign continued toward Richmond.

Aftermath: Although the Wilderness is usually described as a draw, it could be called a tactical Confederate victory, but a strategic victory for the Union army. Lee inflicted heavy numerical casualties (see estimates below) on Grant, but as a percentage of Grant's forces they were smaller than the percentage of casualties suffered by Lee's smaller army. And, unlike Grant, Lee had very little opportunity to replenish his losses. Understanding this disparity, part of Grant's strategy was to grind down the Confederate army by waging a war of attrition. The only way that Lee could escape from the trap that Grant had set was to destroy the Army of the Potomac while he still had sufficient force to do so, but Grant was too skilled to allow that to happen. Thus, the Overland Campaign, initiated by the crossing of the Rappahannock, and opening with this battle, set in motion the eventual destruction of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Therefore, even though Grant withdrew from the field at the end of the battle (which is usually the action of the defeated side), unlike his predecessors since 1861, Grant continued his campaign instead of retreating to the safety of Washington, D.C. The significance of Grant's advance was noted by James M. McPherson.

Both flanks had been badly bruised, and [Grant's] 17,500 casualties in two days exceeded the Confederate total by at least 7,000. Under such circumstances previous Union commanders in Virginia had withdrawn behind the nearest river. Men in the ranks expected the same thing to happen again. But Grant had told Lincoln "whatever happens, there will be no turning back." While the armies skirmished warily on May 7, Grant prepared to march around Lee's right during the night to seize the crossroads village of Spotsylvania a dozen miles to the south. If successful, this move would place the Union army closer to Richmond than the enemy and force Lee to fight or retreat. All day Union supply wagons and the reserve artillery moved to the rear, confirming the soldiers' weary expectation of retreat. After dark the blue divisions pulled out one by one.

But instead of heading north, they turned south. A mental sunburst brightened their minds. It was not another "Chancellorsville ... another skedaddle" after all. "Our spirits rose," recalled one veteran who remembered this moment as a turning point in the war. Despite the terrors of the past three days and those to come, "we marched free. The men began to sing." For the first time in a Virginia campaign the Army of the Potomac stayed on the offensive after its initial battle.

______________________________________________________________

Groping for a Peaceful End to the War

"Sir:

You will proceed forthwith and obtain, if possible, a conference for peace with Hon. Jefferson Davis, or any person by him authorized for that purpose.

You will address him in entirely respectful terms, at all events, and in any that may be indispensable to secure the conference.

At said conference you will propose, on behalf [of] this government, that upon the restoration of the Union and the national authority, the war shall cease at once, all remaining questions to be left for adjustment by peaceful modes. If this be accepted, haustilities to cease at once.

If it be not accepted, you will then request to be informed what terms, if any, embracing the restoration of the Union, would be accepted. If any such be presented you in answer, you will forthwith report the same to this government, and await further instructions.

If the presentation of any terms embracing the restoration of the Union be declined, you will then request to be informed what terms of peace would be accepted; and on receiving any answer, report the same to this government, and await further instructions.

--A. Lincoln"

Autograph draft letter, unsigned, to Lincoln's friend Henry Raymond, Executive Mansion, Washington, August 24, 1864, unsigned

______________________________________________________________________

How many generals did Abraham Lincoln have before he found “winning” U.S. Grant —?

Maj. Gen Winfield Scott: July 5, 1841 - November 1, 1861

Maj. Gen George McClellan: November 1, 1861 - March 11, 1862

Pres Lincoln and War Secretary Stanton (with War Council): March 11, 1862 - July 23, 1862

Maj. Gen Henry W. Halleck: July 23, 1862 - March 9, 1864

Lt Gen Ulysses S. Grant: March 9, 1864 - March 4, 1869

What is often thought of as the main army in the eastern theater, the Army of the Potomac (and thus the field command of the Union Army in the east), went through a series of generals that also differed from this chain:

Brig. Gen Irving McDowell: May 27 - July 25, 1861 (First Battle of Bull Run)

Maj. Gen George B. McClellan: July 26, 1861 - November 9, 1862 (Peninsula Campaign through Antietam)

Maj. Gen Ambrose Burnside: November 9, 1862 - January 26, 1863 (Fredericksburg)

Maj Gen Joseph Hooker: January 26 - June 28, 1863 (Chancellorsville)

Maj. Gen George Meade: June 28, 1863 - June 28, 1865 (Gettysburg through the war's end)

Two issues further complicate this list:

Following the Peninsula Campaign, the Army of the Potomac was divided, with several Corps placed in a new army, the Army of Virginia (led by MG John Pope), which fought the Northern Virginia campaign ending in Second Bull Run. This leads to the appearance of McClellan being removed from command and later recalled, when in reality his command was downgraded.

When Grant was brought east, he was named General in Chief, not commander of the Army of the Potomac. Meade kept command of that army subordinate to Grant, who shared headquarters. Many believe Grant could this way claim the successes of the army while Meade would bear responsibility for operations setbacks. The Eastern armies were further reorganized during this period to add the Army of the James (Butler and Ord) and to reactivation of the Army of the Shenandoah (Sheridan), all working under Lt Gen Grant as both General in Chief and the field commander.

________________________________________________________________________

Every Drop of Blood: The momentous Second Inauguration of Abraham Lincoln, written by Pulitzer Prize finalist, Edward Achorn, reviewed by John S. Gardner, for The Guardian

As Abraham Lincoln prepared to take the oath of office for a second time, on 4 March 1865, the nation waited to hear what he would say about its future. Triumphalism at military success? A call to further sacrifice? Vengeance on the rebel South or an outline for reconstruction?

It was to be none of these things, and thus Lincoln’s Second Inaugural is enshrined in the national memory.